If you’ve been in Paris, you might have noticed how little color is actually worn around. Even the colors I do own in my closet hardly gets worn over the black, white, and grey options; It feels safer, easier, and more comfortable, color draws too much attention.

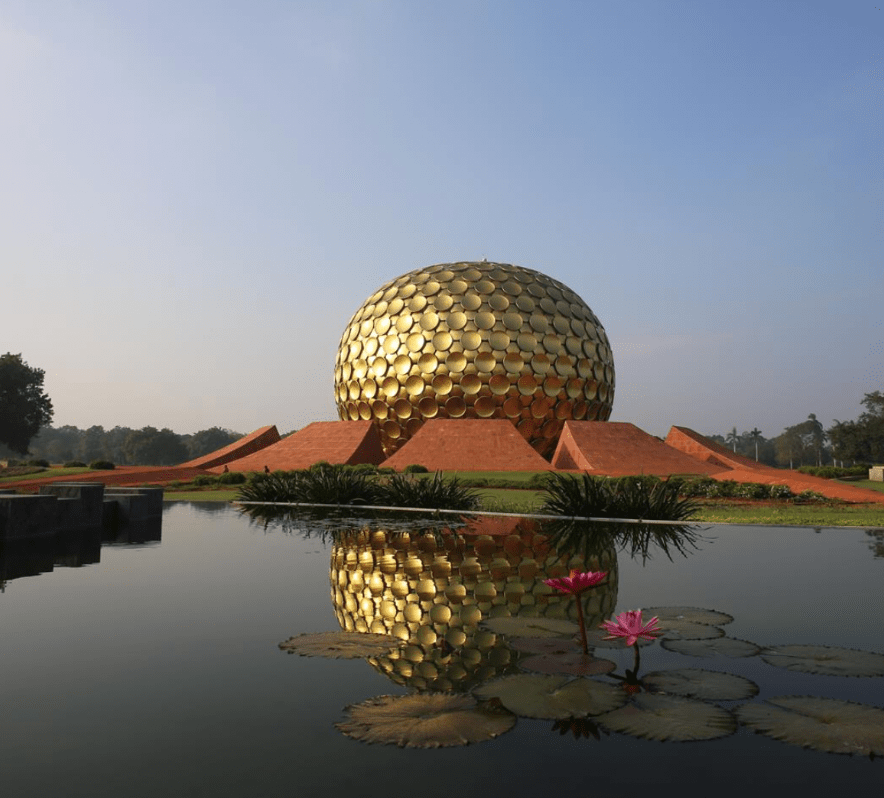

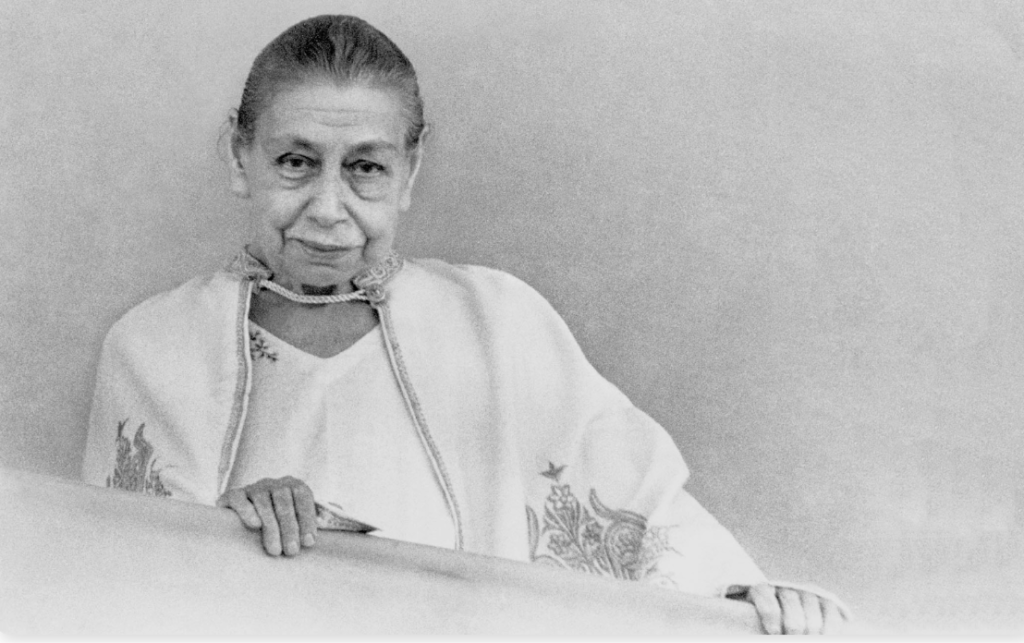

After arriving in Auroville, I don’t think there were many times at all where I saw women without flowers in their hair, dressed in colorful saris or lenghas, and vibrant colorful jewelry. I was first most impressed by the dedication and time that Tamil women put into their appearance, for their hair to be perfectly in place, decorated beautifully and complexly by pinned flowers that somehow manage not to fall out. Lenghas and saris came in more colors than I could ever feasibly imagine to be in my own wardrobe, women I saw consistently such as crocheters and sewers at AVAG came in with different jewelry and scarves to match different saris. On New Year’s Eve, all of the women at AVAG had decided to come to work matching in the same teal blue, I had noticed and complementarily pointed it out, and shared giggles and smiles between the women pursued. These were the kind of experiences that I understood so well without being able to actually understand the language exchanged. I experienced so many times how often women engaged to share feminine experiences with me, putting flowers in my hair, bindis on my forehead and bangles on my wrist; even if we shared no common language, we shared our own language of being a woman.

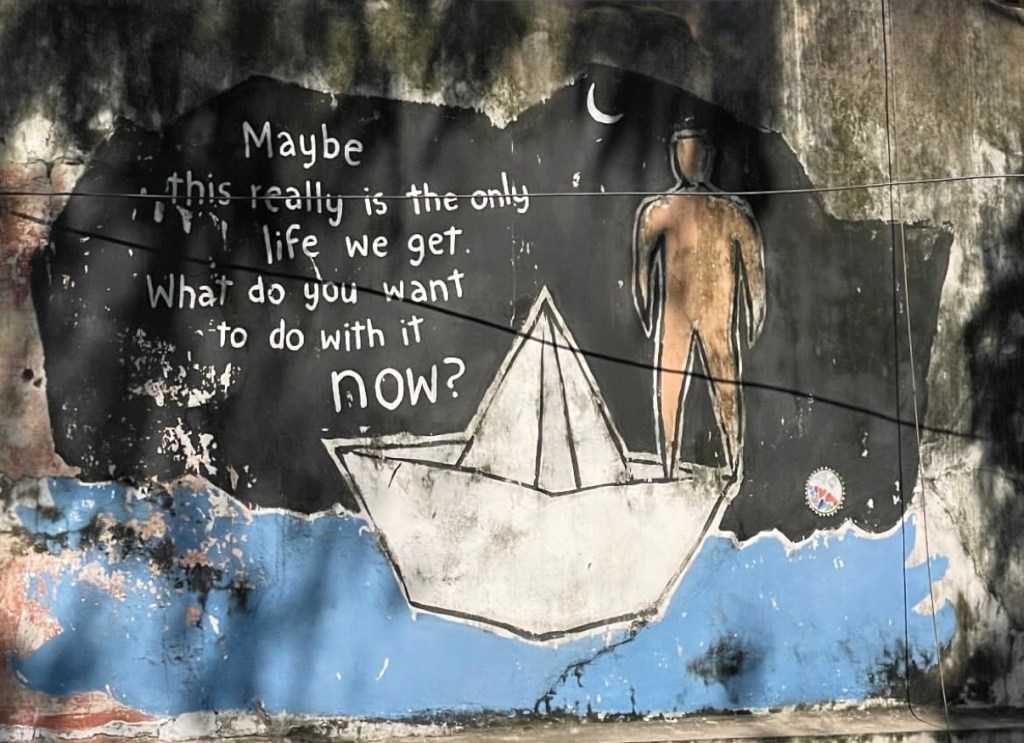

One Auntie, who I had met during an AVAG event, insisted on buying me a pack of bangles from the village shop, I profusely denied her offer until I had no other choice. She asked me which color I liked and I chose the white plastic ones. She looked at me shocked, proceeded to tell me no, and chose a set of blue ones and pointed to my eyes as she gave money to the shop tender and put them on my wrist. I habitually avoid color in my everyday life, but seeing other women embrace it so much, without trying to “seem cool”, and expressing themselves through their appearance so wholeheartedly, and for some, in the only way they can. I then decided that one of my New Years resolutions would be to wear more color, because it’s fun and beautiful, but also a rich tradition cross-culturally for women to express themselves.

A couple of months later, I wore an all pink outfit, something I normally do not do. As I stood at the bus stop on the way to school, an older woman stood next to me, giving me a smile as she looked up and down, a nonverbal communication of femininity and female expression that felt familiar.

by Carol Ann Norris